La intervención de los factores del clima que acabamos de mencionar - particularmente la latitud subtropical y la abundancia de situaciones anticiclónicas sobre la región- determina la existencia en Andalucía de una insolación muy elevada. Todo el valle del Guadalquivir y los espacios costeros, con la excepción del área del estrecho de Gibraltar, supera las 2800 horas de sol al año, sobrepasándose incluso las 3000 horas en algunos enclaves del golfo de Cádiz y la costa almeriense. El resto de la región queda comprendido entre 2800 y 2600 horas de sol, escapando a esta norma sólo los lugares más elevados de los espacios serranos, en los cuales la mayor presencia de nubosidad por efecto del relieve, reduce la insolación por debajo de 2600 horas anuales. Estos altos valores de insolación, asociados al elevado ángulo de incidencia de los rayos solares en estas latitudes tan bajas, determinan también valores elevados de recepción de radiación solar, que superan los 5 Kw/h/m2.

Ambos elementos constituyen, sin duda, dos de los principales recursos que el clima exhibe en el territorio, pero ejercen además una incidencia clara en la configuración de las temperaturas en la región.

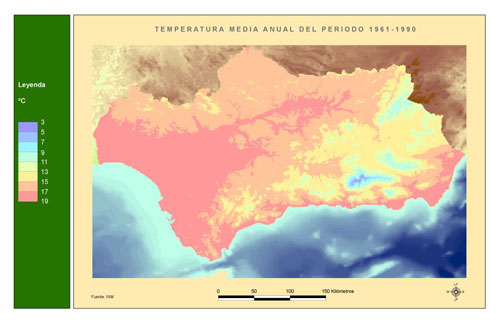

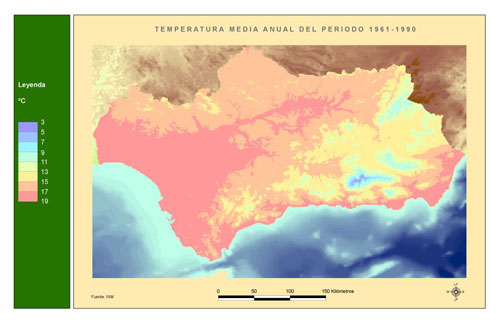

La temperatura media anual adopta valores muy diversos, que reflejan un gradiente costa-interior y, sobre todo, un fuerte gradiente altitudinal, de forma tal que los valores más bajos (inferiores a 9-10°) se encuentran en los enclaves montañosos del interior de las cadenas Béticas (Sierras de Cazorla y Segura, Sierra Nevada...). El flanco occidental de estas cadenas, más abierto a la influencia atemperante del Atlántico, y el conjunto de Sierra Morena, presentan valores más elevados, que oscilan entre 12° y 15°. En la costa atlántica se superan ya los 15°, y en el valle del Guadalquivir y algunos puntos de la costa mediterránea se pueden rebasar los 18°, alcanzándose incluso 20° en algunos enclaves del litoral almeriense, que se constituye en uno de los puntos más cálidos de España.

Figura 1: Temperatura media anual del periodo 1961-1990

Estos valores abstractos, que resultan de la consideración conjunta de situaciones muy diversas a lo largo del año, adquieren algo más de concreción al examinar las temperaturas de enero y julio, expresivas de las condiciones invernales y estivales respectivamente. El mapa de la temperatura media de enero (ver figura 2) dibuja con más claridad aún que el caso anterior los gradientes altitudinales y costa-interior, que son los verdaderos artífices de la temperatura de la región. Los valores más reducidos aparecen siempre en los lugares más elevados, interiores y orientales de la región. Así, todo el conjunto integrado por las Béticas orientales queda por debajo de los 6° de temperatura, destacándose en su interior los lugares más elevados, en los cuales la temperatura suele descender de los 3° e incluso en algunos puntos puede adoptar valores bajo cero. Por el contrario, la porción más próxima al Atlántico del valle del Guadalquivir y los ámbitos costeros registran temperaturas superiores siempre a 9°-10° y a veces, a los 12°.

Figura 2: Temperatura media del mes de enero del periodo 1961-1990

El riesgo de heladas refleja en gran medida este comportamiento de las temperaturas y se muestra como un fenómeno relativamente infrecuente en la región. En ninguna de las áreas no montañosas se superan los 20 días anuales de helada y éstos llegan a ser un fenómeno rarísimo en las zonas costeras, sobre todo en la costa mediterránea, suavizada por el comportamiento térmico del mar interior y protegida de las advecciones de aire frío del norte por las cadenas Béticas. En realidad, sólo adquieren alguna relevancia en las zonas más elevadas, tales como Sierra Nevada y la Sierra de Cazorla, en las cuales se rebasan los 60 días de helada al año. Ello configura en la región un periodo libre de heladas muy prolongado, lo que permite el crecimiento vegetativo de las plantas sin apenas problemas. En la costa mediterránea el periodo libre de heladas supera los 350 días, lo que supone su casi total ausencia, y en todas las zonas costeras más las áreas relativamente llanas, especialmente en la parte occidental, el periodo supera los 250 días anuales. Así pues, sólo en los ámbitos septentrional y oriental de la región, sobre todo en sus enclaves más elevados, se constituyen periodos libres de heladas lo suficientemente cortos como para suponer alguna limitación al desarrollo de la agricultura. También son infrecuentes las olas de frío generalizadas, aunque pueden suceder con ocasión de invasiones de aire polar por advecciones del norte y nordeste, en cuyo caso toda Andalucía, con muy escasas excepciones, puede llegar a soportar temperaturas negativas, alcanzándose valores de 20 y 25° bajo cero en los altiplanos orientales y en la alta montaña (ver tabla 1).

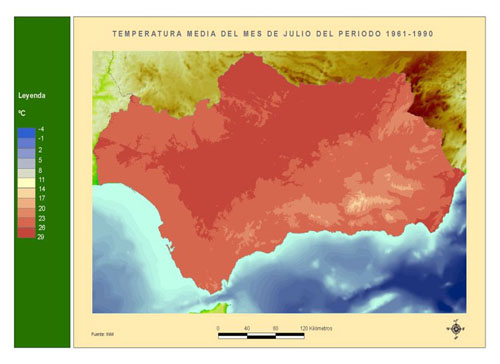

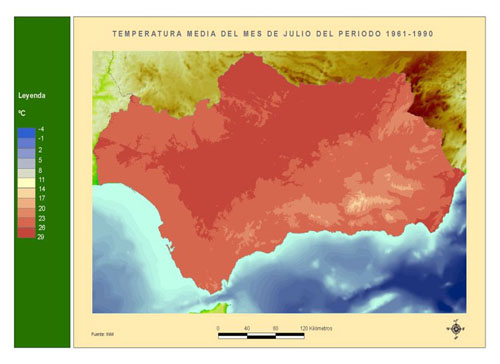

Figura 3: Temperatura media del mes de julio del periodo 1961-1990

Fuente: FONT TULLOT, I. (1983): Climatología de España y Portugal, Madrid, INM y GARCÍA DE PEDRAZA, L. (1985): Estudio de las heladas en España, Madrid, INM.

Durante el verano estas áreas de montaña siguen presentando las temperaturas más bajas (inferiores a 18° en algunos casos), pero ahora las máximas no se encuentran en las zonas costeras, sino en el interior de la región, que no puede beneficiarse de la influencia suavizadora del mar. Todo el interior del valle del Guadalquivir presenta temperaturas medias de julio superiores a 26°, que en algunos reductos llegan a superar los 28°. La elevada magnitud de estos valores - los más altos de España - se comprende adecuadamente si se tiene en cuenta que resultan de la media de temperaturas diurnas y nocturnas. Dado que durante el verano la nubosidad es prácticamente inexistente en la región y la insolación es muy acusada, la amplitud térmica diurna resulta muy elevada, lo que implica que estos valores medios son el resultado de temperaturas diurnas que normalmente superan los 35°. Con ocasión de las invasiones de aire sahariano asociadas a crestas anticiclónicas cálidas en altura , las máximas se sitúan por encima de 40° en la mayor parte de Andalucía y pueden rebasar los 45° en las tierras bajas del interior del valle del Guadalquivir.

Figura 4: Duración del periodo libre de heladas en Andalucía. periodo 1961-1990

Figura 5: Número medio anual de días de helada en Andalucía. periodo 1961-1990

| ESTACIONES | TEMPERATURA MÍNIMA ABSOLUTA (°C) | TEMPERATURA MÁXIMA ABSOLUTA (°C) |

|---|---|---|

| Almería aeropuerto | 0,4 | 41,2 |

| Cádiz | 1,5 | 43 |

| Córdoba aeropuerto | -7,8 | 45,6 |

| Granada aeropuerto | -14,2 | 41,6 |

| Huelva | -0,8 | 43 |

| Jaén instituto | -5,6 | 43,5 |

| Jerez de la frontera base aérea | -5,4 | 44,4 |

| Málaga aeropuerto | -2,6 | 44,2 |

| San Fernando | -2 | 42,6 |

| Sevilla aeropuerto | -4,8 | 45,2 |

| Tarifa | 0,4 | 35,2 |

Fuente: INM (1997): Guía resumida del tiempo en España (1961-90), Madrid.

La amplitud térmica anual refleja el comportamiento conjunto de los mapas de enero y julio y muestra los valores más elevados en el surco intrabético e interior del valle del Guadalquivir, donde se sitúa en 17°-18°, siendo la responsabilidad atribuible en el primer caso a las bajas temperaturas invernales y en el segundo caso a los altos valores estivales. Los ámbitos costeros muestran los valores más reducidos, en torno a 12°-13°, con mínimos en el área del estrecho de Gibraltar, donde se sitúan en torno a 11°.

The intervention of the climate factors that we've just mentioned - particularly the subtropical latitude and the abundance of anticyclonic situations on the region - determines the existence in Andalusia of a high insolation level. All the valley of the Guadalquivir and the coastal spaces, except for the area of the Strait of Gibraltar, are over 2800 sunny hours per year, reaching more than 3000 hours in some locations of the Cadiz Gulf and the coast of Almeria. The rest of the region has between 2600 and 2800 sunshine hours, scaping from these values only the highest areas of mountainous zones, on which the pressence of cloudiness due to the relief, reduces the insolation under 2600 hours per year. These high insolation values, associated to the high incidence angle of solar rays in these low latitudes, also determine high values of solar radiation reception, over 5Kw/h/m2.

Both elements constitute, with no doubt, two of the principal resources that the climate has in the territory, but they have although a clear incidence in the configuration of the region's temperatures.

The annual average temperature adopt varied values that reflect a coast-interior gradient and, over all, a strong altitudinal gradient, making the lower values (less than 9-10°) appear in the mountainous areas of inside the Betic range ( Cazorla y Segura, Sierra Nevada...). The occidental face of these mountain ranges, more openned to the influence of the softening Atlantic, and the conjunction of Sierra Morena, present higher values, variating between 12° and 15°. In the Atlantic coast 15° are passed and in the Valley of the Guadalquivir and some point of the mediterranean coast 18° can be passed, reaching even 20° in some places in Almeria, which is one of the warmest places of Spain.

Figure 1: Annual average temperatures in Andalusia in the period 1961-1990

These abstract values, resulting from the joint consideration of varied situations during the whole year, get more concrete considering the temperatures of January and July, expressive of winter and summer conditions respectively. The January's average value map (see figure 2) draws more clearly than the previous case the altitudinal and coast-interior gradients, which are the real authors of the temperature of the region. The lowest values appear always in the highest interior and oriental locations of the region. In that way, all the oriental Betics are under 6°, standing out inside them the highest places, where the temperature can go under 3° or even values under 0° in some places. In the opposite, the nearest to the Atlantic portion of the Valley of the Guadalquivir and the coastal areas register temperatures always over 9°-10° and, sometimes, over 12°.

Figure 2: Average temperature in January in Andalusia in the period 1961-1990

The risk of frosts reflects this behaviour of temperatures and it's a less frequent phenomenon in the region. In non of the non mountainous areas of the region the annual days of frost are over 20, and they're a really strange phenomenon in coastal zones, specially in the mediterranean coast, softened by the thermical behaviour of the inside sea and protected of the cold air masses advections from the North by the Betic ranges. The truth is that this phenomenon is only relevant in the highest areas, like Sierra Nevada or Cazorla, where there are more than 60 annual frost days. That configures a long period free of frosts in the region, allowing the vegetative growth of the plants without problems. In the mediterranean coast, the free of frost period is over 350 days, what means that there's nearly a total abscence of frosts, and in all the coastal areas plus the relatively flat areas, specially in the occidental part, the period is over 250 days. So, only in the North and West of the region, over all in the highest places, free of frost periods short enough to become a restriction for agriculture take place. Also, there aren't frequent generalized cold spells, but they can happen due to polar air invasions through advections from the north and north-east. When that happens, Andalusia, with very few exceptions, can be at negative temperatures, reaching values of 20° or 25° under cero at the oriental high plateaus and at the highest mountains (see table I).

Figure 3: Average temperature in July in Andalusia in the period 1961-1990

Fuente: FONT TULLOT, I. (1983): Climatología de España y Portugal, Madrid, INM y GARCÍA DE PEDRAZA, L. (1985): Estudio de las heladas en España, Madrid, INM.

During summer these mountainous arear continue having lower temperatures (under 18° in some cases), but now, the maximum temperatures are not at coastal zones, but in the inside part of the region, where the softening effect of the sea has no influence. The whole interior part of the valley of the Guadalquivir presents average temperatures in July over 26°, rising above 28° in some places. The high magnitude of these values - the highest in Spain- is understood right if we take into account that they're the result of the average day an night temperatures. Because the cloudiness during summer is nearly non-existent in the region and the insolation is very pronounced, the daily thermical amplitude results very high, what implies that these average values are the result of daily temperatures that normally rise above 35°. When saharian air masses invasions associated with warm in altitude anticyclonic crests take place, the maximum temperatures rise above 40° in the major part of Andalusia and can reach 45° at the low territories of inside the valley of the Guadalquivir.

Figure 4: Duration of the period free of frost in Andalusia. Period 1961-1990

Figure 5: Average annual frost days in Andalusia. Period 1961-1990

| STATIONS | MINIMUM ABSOLUTE TEMPERATURE(°C) | MAXIMUM ABSOLUTE TEMPERATURE (°C) |

|---|---|---|

| Almería airport | 0,4 | 41,2 |

| Cádiz | 1,5 | 43 |

| Córdoba airport | -7,8 | 45,6 |

| Granada airport | -14,2 | 41,6 |

| Huelva | -0,8 | 43 |

| Jaén Institute | -5,6 | 43,5 |

| Jerez de la frontera air base | -5,4 | 44,4 |

| Málaga airport | -2,6 | 44,2 |

| San Fernando | -2 | 42,6 |

| Sevilla airport | -4,8 | 45,2 |

| Tarifa | 0,4 | 35,2 |

Fuente: INM (1997): Guía resumida del tiempo en España (1961-90), Madrid.

The annual thermical amplitude reflects the joint behaviour of the January and July maps and shows the highest values at the intrabetic furrow and inside the valley of the Guadalquivir, where it situates around 17-18°. We can attribute the responsibility to winter low temperatures in the first case, and to summer high temperature values in the second case. The coastal areas show the most reduced values, around 12-13°, with the minimum values in the Strait of Gibraltar, where they're around 11°.