Además de la panorámica general presentada en el epígrafe anterior, que podría ser atribuible a cualquier espacio ubicado en la cuenca mediterránea, Andalucía presenta rasgos climáticos peculiares que se derivan de la intervención en ella de factores específicos y propios. Entre tales factores merecen destacarse, por un lado, los de carácter termodinámico, ligados al modo de actuación de la circulación atmosférica en el ámbito concreto de la región y, por otro lado, los factores de orden geográfico, entre los cuales el relieve juega el papel primordial, aunque tampoco es desdeñable la acción de la naturaleza de la superficie, en la cual la alternancia de mares y continentes y el propio contraste térmico entre el Atlántico y el Mediterráneo constituyen las piezas clave. Comenzaremos aludiendo a los factores de orden geográfico dado que su influencia llega incluso a plasmarse en los de carácter termodinámico.

Los factores de orden geográfico:

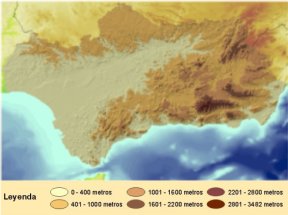

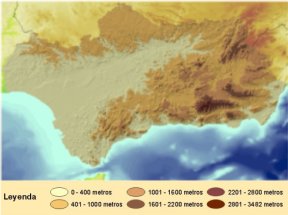

La disposición del relieve y la altimetría constituyen el principal factor de orden geográfico de la región. La mera altimetría interviene fuertemente sobre el clima imponiendo gradientes térmicos altitudinales que consagran a los dominios de montaña como los más frescos de todo el ámbito regional. Los gradientes térmicos altitudinales se pueden evaluar en aproximadamente 0,46°/100 m en la cuenca del Guadalquivir y 0,33°/100 en las solanas de las Béticas, con valores algo más acusados en invierno. Ello determina que las temperaturas más frescas del verano y las más frías del invierno se sitúen en los enclaves más altos de las cadenas Béticas y se vayan suavizando a medida que se desciende hasta el nivel del mar.

Figura 1: Altimetría de Andalucía

Pero, además, la disposición del relieve ejerce fuertes repercusiones sobre el clima de la región. El relieve andaluz presenta una orientación general SW-NE, especialmente marcada en las cadenas Béticas, en las cuales se sitúan además la alturas más elevadas, superándose los 3000 metros sobre el nivel del mar. En este edificio sólo se registra una gran apertura en el valle del Guadalquivir, a la que acompañan otras muy inferiores constituidas por las depresiones litorales mediterráneas y algunas planicies interiores emplazadas en el surco intrabético. Todo ello tiene repercusiones climáticas destacables. En primer lugar, el predominio de las influencias marinas atlánticas sobre las mediterráneas. Estas últimas quedan reducidas al ámbito estrictamente costero salvo las pequeñas penetraciones que encauzan los valles que vierten a esta cuenca y que sólo alcanzan cierto desarrollo y amplitud en el levante almeriense. Sin embargo, la influencia atlántica encuentra para su penetración el amplio valle del Guadalquivir, que se encuentra en una perfecta disposición para recoger y canalizar hacia el interior de la región los vientos del W y SW, que son por otra parte los predominantes durante la estación invernal y, más genéricamente, en el periodo comprendido entre octubre y junio.

En segundo lugar, la fragmentación de la región en dos grandes ámbitos climáticos bien diferenciados: el noroccidental o atlántico y el suroriental o mediterráneo, separados grosso modo por las cadenas Béticas, que se convierten en una muralla más o menos infranqueable entre uno y otro dominio. Esta fragmentación constituye un rasgo interno esencial del clima de la región, sobre todo, por la escasa covariación existente entre ambos dominios. La disimetría es especialmente marcada en la precipitación, donde el ámbito noroccidental suele recibir lluvia a través de mecanismos atlánticos (frentes y perturbaciones que penetran desde el oeste) que no llegan a hacerse sentir a sotavento de las Béticas, mientras que el suroriental las recibe a través de depresiones mediterráneas que tampoco alcanzan, en general, a los ámbitos noroccidentales. Pero las temperaturas y la humedad también acusan esta disimetría como consecuencia del efecto föhn ejercido por esta cadena sobre los vientos de procedencia tanto atlántica y septentrional como mediterránea y meridional.

El relieve, además, contribuye a configurar un área muy continentalizada en el interior de la región (las hoyas interiores de las cadenas Béticas y, en general, todo el surco intrabético), donde tanto las influencias atlánticas como las mediterráneas se ven obstaculizadas para acceder. Los extremos térmicos y la exigüidad pluviométrica serán buena muestra de este carácter continental. Por último, el relieve, por su peculiar disposición SW-NE y en buena medida W-E, genera importantes disimetrías térmicas entre las solanas y las umbrías, las primeras con abundante recepción de radiación solar y protegidas de las invasiones frías del norte por el relieve y, en consecuencia muy beneficiadas térmicamente, y las últimas con la situación justamente contraria. Toda la alineación de Sierra Morena constituye un buen ejemplo de este tipo de solanas, pero el ejemplo arquetípico se sitúa en la vertiente sur de las cadenas Béticas, donde a la condición de solana se asocia la influencia termorreguladora del Mediterráneo, todo lo cual la convierte en uno de los dominios más cálidos y suaves del continente europeo.

A todo ello habría que añadir los efectos ejercidos a escalas más detalladas, que no serán objeto de la presente obra, pero entre los cuales habría que destacar por su importancia las modificaciones ejercidas sobre el viento en el área del estrecho del Gibraltar y sus proximidades como consecuencia del encajamiento del aire en el angosto pasillo que allí dibuja el relieve. La naturaleza de la superficie constituye un factor geográfico menos importante pero digno también de ser tomado en consideración, destacando en este sentido la presencia de la franja marina que rodea a la región por su flanco meridional y la ligera disimetría existente entre el área atlántica y el área mediterránea de dicha franja.

El Atlántico, en las proximidades de las costas andaluzas, tiene una temperatura media que oscila entre unos 14-15° en enero y unos 20-21° en julio. Por su parte, el Mediterráneo iguala esa cifra en enero, pero la supera en agosto, alcanzando entonces 22,5-23° de temperatura y, de hecho, a igualdad de latitud, siempre el Mediterráneo alcanza temperaturas superiores a las del Atlántico a excepción del invierno. Además, estos valores térmicos elevados se mantienen en el Mediterráneo a lo largo de todo su espesor, que alcanza aproximadamente 4000 m. y en el que no se desciende en general por debajo de 13°. Estos altos valores de temperatura son atribuibles a la fuerte insolación que la zona recibe a lo largo de casi todo el año y especialmente en verano, pero son atribuibles también a la condición que el Mediterráneo presenta de cuenca pequeña, cerrada y poco comunicada con el Atlántico.

Dos consecuencias importantes se derivan de estas elevadas temperaturas : en primer lugar, el efecto de atemperación ejercido en las zonas costeras, el cual es especialmente palpable en el invierno y, sobre todo, el hecho de que el Mediterráneo se convierte en una gran reserva de vapor de agua susceptible de trasvasarse hacia la atmósfera con ocasión de los movimientos ascensionales. Estos trasvases de vapor, y los de calor latente que llevan asociados, adquirirán un carácter protagonista en la génesis de ciertas perturbaciones atmosféricas especialmente relevantes durante la estación otoñal, como tendremos ocasión de comprobar más adelante.

Instead of the general view presented in the previous point, that could be attributed to any region in the mediterranean basin, Andalusia has peculiar climatic features deriving from the influence on it of specific factors. Among those factors, we have to emphasize, on one side, the thermodynamic ones, connected to the action mode of atmospheric circulation in the concrete area of the region, and, on the other side, the geographical factor, among which the relief has a fundamental role, although the action of the nature of the surface, on which the alternation between seas and continents and the thermal contrast between the Atlantic and the Mediterranean are the key features, is also important. We'll begin talking about the geaographical factors because their influence is even on the thermodynamic factors.

The geographical factors

The relief layout and the altimetry costitute the most important geographical factor of the region. The altimetry has a strong influence on the climate, imposing altitudinal thermical gradients that make the mountain's domains the coolest of the region. The altitudinal thermical gradients can be evaluated approximately in 0'46°/100m in Guadalquivir's basin and 0'33°/100m in the Betic suntraps, with more marked values in winter. These factors determine tha tthe cooler temperatures of summer, and the coldest of winters are located in the highest of the Betics and they soften as we go down to the sea level.

Figure 1: Andalusian altimetry

But, overmore, the arrangement of the relief has a strong influence on the region's climate. Andalusian relief has a general SW-NE orientation, specially noticeable in the Betic chains, on which also the highest altitudes, exceding 3000 meters over sea level, are located. In this building, only a big opening is registered in the Valley of the Guadalquivir, accompanied by others quite inferiors constituted by the mediterranean coast depressions and some palne zones located in the intrabetic furrow. All these factors have repercussions on climate. In first place, the predominance of marine atlantic influences over mediterraneans. These ones are reduced to the coastal areas except for the for the small penetrations channeled by the valleys that spill in this basin and which only get some importance in the East part of Almería. Even though, the atlantic influence finds the wide Valley of the Guadalquivir for its penetration, which is in a perfect arrangement to collect and channel to the inside part of the region the W and SW winds, which are, on another side, predominant during the winter season, and more generically, in the period between October and June.

In second place, the fragmentation of the region in two well differentiated climatic fields: the noroccidental or atlantic and the southoriental or mediterranean, separated by the Betic chains, converted in a more or less impassable wall between both domains. This fragmentation constitutes an essential internal feature of the climate of the region, most of all, because of the scarce covariation existing between both domains. The asymmetry is specially marked in the rainfall, where the noroccidental area receives rainfalls through the atlantic mechanisms (fronts and perturbations penetrating from the West) that don't reach the Betic leeward, whereas the southoriental region receives them through the mediterranean depressions that also don't reach, generally, the noroccidental regions. But temperatures and humidity are also affected by this asymmetry as a consequence of the föhn effect exerted by this chain on the winds coming from the Atlantic and the North, and from the Mediterranean and the South.

The relief, overmore, contributes to configure a very continentalized area in the inside part of the region ( the interior hollows of the Betic chains, and generally, all the intrabetic furrow),where both the atlantic and the mediterranean influences cannot access. The thermal extremes and the pluviometric scarce are a good indicator of this continental nature. Finally, the relief, due to its peculiar SW-NE arrangement and W-E in part, generates important thermical asymmetries between suntraps and shadies, the former with abundant reception of solar radiation and protected from the cold invasions from the North by the relief and, in consequence, greatly benefitted thermicaly, and the latter with exactly the opposite situation. All the alignment of Sierra Morena constitues a good example of this type of suntraps, but the archetypic example is located in the South face of the Betic chains, where the thermoregulator influence of the Mediterranean is associated to the condition of suntrap, all converting it in one the hottest and softest region of the European continent.

We should add to all these factors the effects that take place in a more detailed scale, that won't be aim of this work. Anyway, among them we should consider due to its importance, the changes on the wind in the Strait of Gibraltar and its surrounding areas as a consequence of the fitness of the air in the narrow corridor that the relief draws there. The nature of the surface constitutes a less important geographical factor, but also noticeable, standing out in that sense the presence of the marine strip that surrounds the region on the South and the small asymmetry existing between the Atlantic and the Mediterranean areas of this strip.

The Atlantic Ocean, near Andalusian coasts, has an average temperature that vary between 14-15° in January and 20-21° in July. On its side, the Mediterranean Sea equals those temperatures in January, but exceeds them in August, reaching 22'5-23° and, in fact, at same latitudes, the Mediterranean always has higher temperatures than the Atlantic, except in winter. Overmore, these high thermal values are a constant in the Mediterranean along all its thickness, that reaches nearly 4000m and where the temperature generaly is never under 13º. These high temperature values can be attributed to the strong insolation that the region receives during the whole year and specially in summer, but they can also be attributed to the small and closed basin conditions of the Mediterranean and its little communication with the Atlantic Ocean.

Two important consequences derive from these high temperatures: in first place, the soften effect exerted on the coastal areas, which specially palpable in winter and, over all, the fact that the Mediterranean becomes a water vapor reserve that can be transferred to the atmosphere due to the ascending movements. These vapor transfers, and the latent heat transfers associated, will have a principal role in the generation of some atmospheric perturbations specially relevant during the autumn season, as we'll sea later.