Los factores de orden termodinámico son aquéllos ligados al modo de actuación de la circulación atmosférica en el ámbito concreto de la región. En este sentido, el hecho más destacable es que la posición de Andalucía en el flanco más meridional de las latitudes medias determina una cierta marginalidad respecto al flujo circumpolar del oeste que recorre en altura estas latitudes y que es el principal responsable del tiempo en la zona. Como consecuencia de ello la región prácticamente nunca se ve sometida al flujo del oeste en disposición zonal, sino que recibe su visita cuando éste adopta un flujo meridiano o incluso cuando adopta circulaciones celulares cerradas. Además, hay que señalar que éstas últimas tienen una predisposición particular a situarse en las inmediaciones del estrecho de Gibraltar y golfo de Cádiz, siendo éste también un lugar preferente para el establecimiento de vaguadas profundas.

Es también reseñable en nuestro ámbito la necesidad de establecer una distinción muy clara entre los tipos de circulación que se establecen durante el verano de los que caracterizan a las restantes estaciones. En el primer caso el desplazamiento hacia el hemisferio Norte de todos los anillos que componen la circulación general atmosférica determina que en nuestro ámbito se ubique de manera permanente el cinturón de altas presiones subtropicales y, más concretamente, la célula conocida como anticiclón de las Azores. En esta estación, pues, el vórtice circumpolar

queda muy desplazado hacia el norte y el flujo circumpolar del oeste o corriente en chorro se sitúa por encima del paralelo 45° N, dejando a Andalucía fuera de su radio de acción. Ello supone un predominio casi absoluto de la estabilidad. En invierno los anillos de la circulación atmosférica se desplazan hacia el sur y la corriente en chorro puede alcanzar los paralelos 35-45° con disposición zonal o incluso latitudes más bajas con disposiciones meridianas. En estos casos las situaciones de estabilidad e inestabilidad se suceden alternativamente y asistimos a la invasión de masas de aire no sólo tropicales sino también polares e incluso árticas, si bien éstas últimas llegan muy desnaturalizadas a Andalucía.

Ambas razones son las que nos han empujado a presentar los tipos de tiempo o situaciones sinópticas dominantes en la región a partir de una primera consideración acerca del comportamiento del flujo circumpolar del oeste en las capas altas de la atmósfera y a partir, también, de una diferenciación estacional, distinguiendo básicamente los tipos de tiempo veraniegos de aquellos que se presentan en las restantes estaciones del año.

Los tipos de tiempo dominantes en verano

El hecho común a todos los tipos dominantes en verano es el desplazamiento de la corriente en chorro hacia latitudes muy altas, que deja a la región andaluza sometida al cinturón de altas presiones subtropicales. Las escasas variaciones que se producen dentro de esta tónica general se derivan de pequeños matices que se introducen en la configuración de las presiones tanto en altura como en superficie. Dos son las situaciones que se repiten con más frecuencia en esta estación:

Cresta anticiclónica en altura y pantano barométrico en superficie

Las altas presiones subtropicales están bien extendidas por el hemisferio norte, cubriendo la península Ibérica una cresta anticiclónica muy cálida que garantiza la estabilidad en toda Andalucía. Como reflejo de esta situación, en superficie se extiende un enorme anticiclón que cubre todo el Atlántico y buena parte del continente europeo y que sobre le península Ibérica dibuja un pantano barométrico con presiones próximas a la normal e isobaras muy separadas que ponen de manifiesto el escaso gradiente barométrico y la calma que reinan en todo el territorio. Al no existir ningún flujo del norte en la península se produce un predominio absoluto de la masa tropical continental, muy recalentada; ello, unido a la fuerte estabilidad atmosférica reinante, que impide los intercambios verticales del aire, propicia la aparición de temperaturas muy elevadas en casi todo el territorio español y en especial en Andalucía, donde un régimen de levante muy calmado puede ocasionar que se rebasen los 40° en el interior de la región y valle del Guadalquivir.

Es un tipo de tiempo que se puede originar en todo el periodo comprendido entre mayo y octubre, aunque especialmente frecuente en julio y agosto. Su duración es larga y puede prolongarse durante más de una semana sin interrupción.

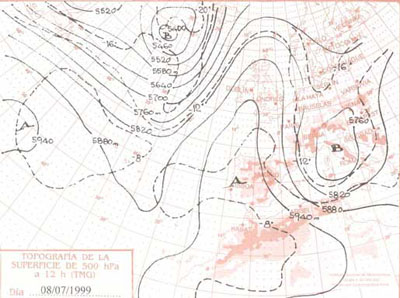

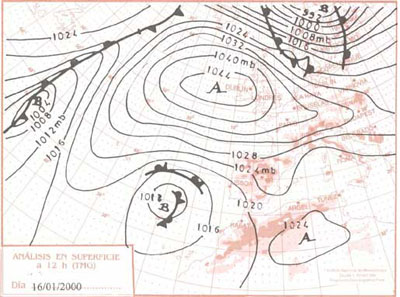

Figura 1: Mapas del tiempo e imagen meteosat correspondientes al 08 de julio de 1999

Depresión térmica superficial asociada a una ligera vaguada en el seno del alta subtropical de las capas altas de la atmósfera

En el mapa correspondiente al día 18 de agosto de 1999, la corriente en chorro continúa viajando por latitudes muy elevadas, pero una pequeña vaguada con su correspondiente irrupción de aire más frío se desplaza hasta latitudes próximas al paralelo 30° N. En el suelo una depresión de origen térmico, que prolonga la depresión sahariana, se instala sobre el sur peninsular introduciendo hacia Andalucía la masa de aire tropical continental con claro flujo de levante. El calor es también intenso en la región con estas situaciones, si bien ahora el intercambio vertical del aire es más fuerte por la existencia de la depresión superficial y la menor estabilidad reinante en altura, lo cual contribuye a suavizar algo el rigor térmico. Ello no impide la reducción de la visibilidad por calima y la invasión de polvo sahariano. Cuando la vaguada de altura se instala convenientemente sobre la región propiciando la superposición de aire frío sobre el aire cálido superficial, pueden llegar a desencadenarse brotes convectivos y tormentas, que originan un importante descenso de las temperaturas y proporcionan los escasos días de precipitación que pueden llegar a producirse en el verano de nuestra región.

El establecimiento de la depresión térmica superficial sobre Andalucía, como prolongación de la del Sahara, constituye la situación más frecuente del verano; por el contrario, dada nuestra posición meridional, el embolsamiento de aire frío en altura se da sólo muy esporádicamente, especialmente en el corazón del verano, de ahí el carácter tan prolongado y continuo de la sequía estival, muy superior a la registrada en las restantes regiones españolas.

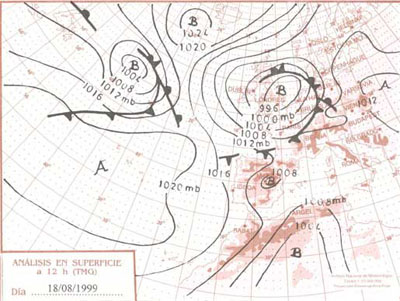

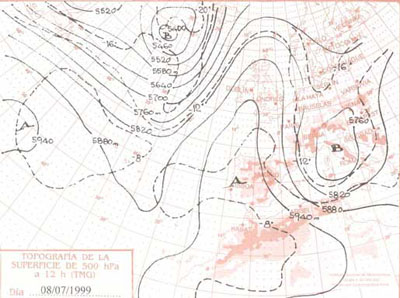

Figura 2: Mapas del tiempo e imagen meteosat correspondientes al 18 de agosto de 1999.

Los tipos de tiempo dominantes en invierno

Durante el invierno -entendido lato sensu como el periodo comprendido entre octubre y junio- las situaciones sinópticas son más variadas, lo que explica la mayor variabilidad del tiempo en esta época. Estas variaciones están ligadas esencialmente al comportamiento del flujo circumpolar del oeste, que puede revestir tres formas básicas: circulación zonal, meridiana y celular.

Los tipos de tiempo ligados a la circulación zonal en la corriente en chorro

El hecho más común es que la circulación se establezca al norte de la península, recorriendo su flanco más meridional los paralelos 40-45° 8 de febrero de 2000. Ello determina que buena parte de España (a excepción de la fachada norte) y, desde luego, la región andaluza, queden bajo la influencia de altas presiones en altura que se acompañan también en superficie por un anticiclón extendido en el sentido de los paralelos. El aire tropical marítimo o el polar marítimo muy suavizado llegan entonces hasta nuestra región propiciando un tiempo estable y soleado, con ausencia de precipitaciones y escasa o nula nubosidad, salvo la asociada a las nieblas matinales que propicia la estabilidad.

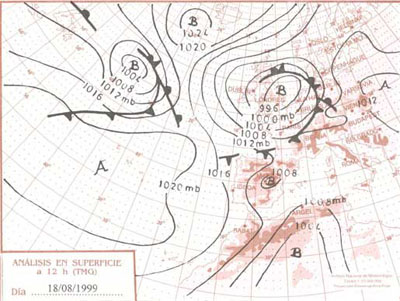

Figura 3: Mapas del tiempo e imagen meteosat correspondientes al 08 de febrero de 2000.

Es un tipo de tiempo persistente (suele durar más de cinco días) y, aunque puede producirse en cualquier mes del año, tiene su máxima frecuencia de diciembre a marzo.

Con mucha menos frecuencia el flujo circumpolar del oeste se centra en los paralelos 35-40°, recorriendo entonces las perturbaciones del frente polar el conjunto de la península de oeste a este 25 de diciembre de 2000. En su flanco meridional afectan a Andalucía y pueden producir allí precipitaciones, acompañadas de temperaturas suaves derivadas de la intervención sobre la región, también en este caso, de masas de aire tropicales marítimas alternando con polares marítimas muy suavizadas por su largo recorrido oceánico. La frecuencia de este tipo de tiempo no es muy elevada, pero puede producirse entre diciembre y febrero, propiciando entonces la aparición de sucesivos días lluviosos y muy suaves en términos térmicos.

En ocasiones el flujo circumpolar del oeste ondula ligeramente y atraviesa la península junto con las perturbaciones del frente polar, en dirección noroeste-sureste, quedando las altas presiones relegadas a una posición más occidental. En estas situaciones las perturbaciones también barren el conjunto de la región, incluso el sureste, aunque ahora las temperaturas son inferiores a las del tipo precedente como consecuencia de la trayectoria más septentrional seguida por el aire polar marítimo, el único que ahora nos visita.

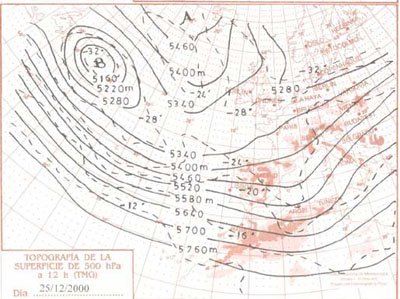

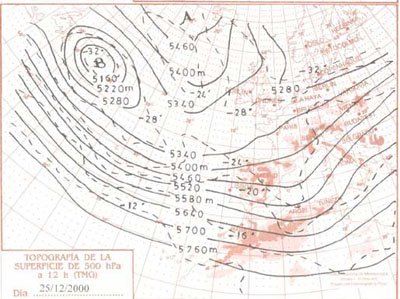

Figura 4: Mapas del tiempo e imagen meteosat correspondientes al 25 de diciembre de 2000.

Los tipos de tiempo ligados a la circulación meridiana de la corriente en chorro

Los regímenes de la circulación zonal de la corriente en chorro, que corresponden a índices altos de circulación, se alternan con otros en los que el chorro presenta índices de circulación bajos y adopta posiciones meridianas, dibujando crestas y vaguadas más o menos pronunciadas. La posición de estas crestas y vaguadas sobre un territorio es determinante del tiempo que se registra en él; las vaguadas comportan advecciones de aire frío e inestabilidad, la cual es excepcionalmente marcada en el flanco oriental; por su parte, las crestas anticiclónicas transportan aire cálido hacia latitudes altas y las someten a un régimen de estabilidad atmosférica, más marcada también en su flanco oriental. Como consecuencia de esta disimetría es frecuente que en Andalucía se produzcan situaciones de diferenciación oeste-este o Andalucía occidental-oriental con ocasión de estas situaciones.

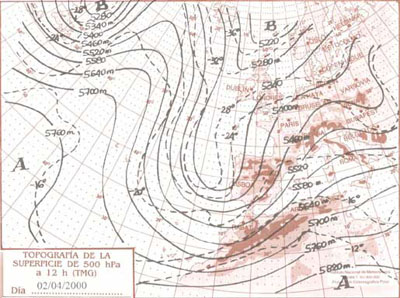

En el mapa del 2 de abril de 2000 la situación dibuja una vaguada sobre la península, con eje central en torno al golfo de Cádiz. Toda España, y particularmente el suroeste, se ve sometida a una fuerte inestabilidad, que en superficie se traduce en una profunda borrasca con centro en el paralelo 45°. Dos frentes fríos muy activos la acompañan, barriendo la península de suroeste a nordeste. En su inicio esta borrasca canaliza aire tropical marítimo procedente del suroeste hacia Andalucía y propicia temperaturas relativamente suaves para la época del año, acompañadas de precipitaciones intensas. Tras el paso de los frentes es el aire polar marítimo, con recorrido norte-sur, el que se impone, determinando una bajada brusca de las temperaturas. Toda la región se encuentra sometida a lluvias, que pueden llegar a ser muy intensas en el golfo de Cádiz, especialmente en los enclaves montañosos más occidentales, en los que el efecto de disparo ejercido por el relieve se une al mecanismo termodinámico.

No suele ser un tipo de tiempo muy duradero (3-4 días) ni tampoco muy frecuente, produciéndose sobre todo en invierno y comienzos de la primavera.

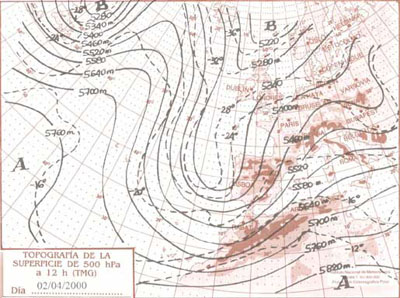

Figura 5: Mapas del tiempo e imagen meteosat correspondientes al 02 de abril de 2000.

Una situación también de vaguada, pero ahora alojada en el Mediterráneo se registró el 8 de abril de 1999. En este caso la zona de máxima inestabilidad estaba en el área oriental de la península, debajo del flanco delantero de la vaguada, lo cual se reflejó en la formación de una depresión bien excavada sobre el golfo de Génova. En el Atlántico, bajo la cresta de la corriente en chorro, se originó un anticiclón de bloqueo también muy potente (1032 hPa en su centro) y entre ambos se canalizaba un flujo del norte y nordeste que transportaba aire polar hacia la península, procedente del continente eurosiberiano. El ambiente en toda la región fue muy frío y seco, la nubosidad estuvo prácticamente ausente, salvo por la aparición de nieblas de irradiación nocturna en los valles, favorecidas por la estabilidad atmosférica, y las temperaturas mínimas alcanzaron los valores más bajos de la región por la presencia de la masa de aire polar continental y por las fuertes pérdidas de calor por irradiación, al no existir en la atmósfera suficiente vapor de agua para retenerlo.

Se trata de tipos de tiempo cuya duración se establece en unos tres a cinco días y cuya frecuencia no es desdeñable en ningún mes del año a excepción de la estación estival.

Figura 6: Mapas del tiempo e imagen meteosat correspondientes al 08 de abril de 1999.

Los tipos de tiempo ligados a circulaciones celulares de la corriente en chorro

Cuando el índice de circulación se hace muy bajo y los meandros descritos por la corriente en chorro se pronuncian mucho, llegan a formarse circulaciones celulares o cerradas que forman en altura grandes anticiclones cálidos desplazados hacia latitudes muy altas y depresiones de aire frío que se sitúan en las latitudes bajas. Lo acusado de los meandros obliga al chorro a abandonar estas bolsas de aire cálido y frío, reconstituyéndose en las latitudes más septentrionales. En estas circunstancias, Andalucía, por su posición meridional, recibe la influencia de los embolsamientos de aire frío en altura, que inmediatamente generan una fuerte inestabilidad atmosférica. En estas condiciones tienden a formarse sobre la región los denominados "conjuntos convectivos de mesoescala", que no son sino desarrollos tormentosos multicelulares de gran extensión (el radio suele ser superior a 100 kms.), normalmente con excentricidad en su radio y con una duración que supera ampliamente la que caracteriza a las típicas tormentas estivales. Estas formaciones nubosas, con una estructura bien organizada, se generan a partir de la coalescencia de núcleos convectivos iniciales en un contexto de abundante vapor de agua en la atmósfera y de fuerte inestabilidad, rasgos todos que caracterizan a estos embolsamientos de aire frío en altura a los que estábamos aludiendo.

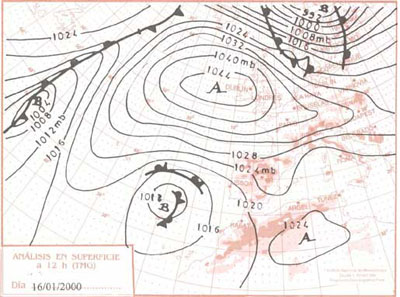

Dos son los lugares preferentes para la instalación de estas depresiones frías: el golfo de Cádiz y norte del archipiélago canario y el Mediterráneo occidental. El primer caso aparece ejemplificado en el mapa del 16 de enero de 2000. En él una ondulación muy marcada de la corriente en chorro abandona un anticiclón de bloqueo en el Atlántico norte y un importante embolsamiento de aire frío entre Canarias y el golfo de Cádiz. Las isohipsas cerradas en círculo en torno a la depresión y la bajísima temperatura del aire en su seno configuran a esta baja como una gota fría, diagnóstico que se confirma al comprobar el escaso reflejo que esta baja adquiere en superficie. En efecto, en el mapa de superficie una baja presión relativa de 1012 hPa se sitúa por debajo de la gota. La presión apenas difiere de la presión normal, pero se ha generado una bien marcada curvatura ciclónica en el área meridional de la península que, asociada a la baja de altura, desencadenará una importante inestabilidad, con aparición de lluvias generalizadas en Andalucía y especialmente en el entorno del estrecho de Gibraltar.

Figura 7: Mapas del tiempo e imagen meteosat correspondientes al 16 de enero de 2000.

El 12 de enero de 2001 es una difluencia de la corriente en chorro la que provoca el desprendimiento de una depresión fría hacia el sur de la península Ibérica, centrándose en esta ocasión sobre el Mediterráneo. Su reflejo en superficie es ahora más marcado que en el caso anterior, situándose una depresión sobre la costa mediterránea peninsular. El embolsamiento de aire frío en altura, sobre las aguas del Mediterráneo, relativamente cálidas, genera un gradiente térmico vertical muy inestable que, asociado al fuerte contenido de vapor de agua de la atmósfera, desencadena intensas precipitaciones en todo el levante peninsular, especialmente en las laderas montañosas situadas a barlovento. La Andalucía mediterránea es ahora la más afectada por las lluvias, quedando la zona occidental bajo el abrigo constituido por la cresta anticiclónica del Atlántico.

Todos estos tipos que genéricamente hemos atribuido a la estación invernal pueden producirse en cualquiera de los meses comprendidos entre octubre y junio. Hay que destacar, sin embargo, que los asociados a las circulaciones meridianas y celulares adquieren una importancia especial en las interestaciones, en las cuales se produce el reajuste entre las circulaciones invernal y estival de la corriente en chorro y de todos los centros de acción que la acompañan. Estos reajustes implican la continua formación de meandros en el flujo circumpolar del oeste, con crestas y vaguadas sucediéndose sobre el territorio andaluz. Como consecuencia de ello el tiempo suele ser más variable que en el corazón del invierno o el verano, y los tipos de tiempo suelen ser también menos persistentes. Por otro lado, no es infrecuente que se alternen primaveras u otoños que prolongan la estación que los precede (los otoños secos que prolongan las situaciones típicas del verano no son extraños a la región, por ejemplo) con otros que adelantan la estación que les sucede (sería el caso de los otoños en los que las lluvias se instalan precozmente, ya desde los inicios o mediados del mes de septiembre).

En un intento de síntesis de las situaciones que caracterizan a cada estación del año, podríamos describir el verano como la estación de claro predominio de las situaciones anticiclónicas, con sólo pequeñas depresiones térmicas muy débiles y sin apenas reflejo en el tiempo experimentado, y como la época de mayor duración de los tipos de tiempo, los cuales pueden llegar a prolongarse hasta dos o tres semanas ininterrumpidamente. En invierno los tipos ciclónicos y anticiclónicos presentan frecuencias similares, en torno al 50% en cada caso, y ambos adquieren una fuerte intensidad y una duración prolongada. La primavera registra un predominio de las situaciones ciclónicas, que serán además bastante duraderas en relación con la fugacidad de las situaciones anticiclónicas. El tiempo presenta además una máxima variabilidad, con tipos ciclónicos poco intensos alternando con otros más intensos y con tipos anticiclónicos. Por último, el otoño constituye una época de transición al invierno y en esa medida podría ser dividida en dos partes bien diferenciadas: el mes de septiembre y comienzos de octubre, que tendería a prolongar las características estivales, y la segunda parte de octubre y el mes de noviembre, que se asimilarían ya al funcionamiento propio del invierno. En esta estación hay que destacar, además, la aparición frecuente de paroxismos pluviométricos asociados a la presencia de gotas frías, muy activas en esta época del año como consecuencia de las altas temperaturas que entonces se alcanzan en el Mediterráneo. Estas elevadas temperaturas propician gradientes térmicos verticales muy inestables y un trasvase importante hacia la atmósfera de vapor de agua y de calor latente, todo lo cual favorece el desarrollo de esas precipitaciones tan intensas.

Thermodynamical factors are those associated with the behaviour of the atmospheric circulation in the region.In this sense, the most noticeable fact is that the Andalusian position in the Southern part of medium latitudes determines a certain marginality respect to the west circumpolar flow that travels over this latitudes at high altitudes and which is the responsible of the weather in the region. As a consequence, the region is practically never influenced by the west flow in zonal arrangement, but receives its visit when it adopts a southern flow or even when it adopts closed cellular circulations. Overmore, we have to mention that these last ones have a particular predisposition to locate near the Strait of Gibraltar and the Gulf of Cadiz, being this also a preferent place for the establishment of deep watercourses.

It is also noticeable in our field the necessity to establish a clear distinction among the circulation types established during summer which influence the other seasons. In the first case, the movement towards the North Hemisphere of all the rings that compose the general atmospheric circulation determines that the subtropical high pressures strip is permanently located in our region and, specifically, the cell known as the Azores anticyclone. Then,in this season, the circumpolar vortex is moved up to the North and the West circumpolar flow or jet stream is located over the 45°N parallel, leaving Andalusia out of its influence. That means a nearly absolute predominance of stability. In winter the circulation rings move towards the South and the jet stream can reach the 35-45° parallels with zonal arrangement or even lower latitudes with

meridian arrangements. In these cases the stability and instability situations succeed alternatively and we have the invasions of air masses not only tropical, but polar and even artic, although these last ones arrive to Andalusia quite denaturalized.

Both reasons have motivated that we present the climate types or dominant synoptic situations in the region from a first consideration about the behaviour of the West circumpolar flow in the high layers of the atmosphere and also from a seasonal differentiation, basically distinguishing the summer weather types from those present in the rest of the seasons.

Weather types dominant in summer

The common feature to all summer dominant types is the movement towards high latitudes of the jet stream, that leaves the region under the influence of the subtropical high pressures strip. The scarce variations that take place in this general behaviour derive from small features introduced in the configuration of pressures in altitude and surface. Two are the situations most frequently repeated in this season:

Anticyclonic crest in altitude and barometric swamp in surface

The subtropical high pressures are well extended in the North hemisphere, covering the Iberian peninsula a very warm anticyclonic crest that guarantees the stability in all Andalusia. As a reflection of this situation an enormous anticyclone that covers all the Atlantic and an important part of the European continent is extended in surface, drawing a barometric swamp over the Iberian peninsula with pressures near to normal values and quite separated isobars that show the scarce barometric gradient and the generalized calm in all the territory. Because there isn't any flow from the North in the peninsula the tropical continental mass is absolutely dominant, quite reheated; that, and the general atmospheric stability, taht doesn't allow vertical air interchanges, favours the appearing of high temperatures in all the Spanish territory and specially in Andalusia, where a quite calmed east wind regime can make the temperatures go over 40° in the inside parts of the region and in the valley of the Guadalquivir.

This is a type of weather that can take place in the whole period between May and October, although it's specially frequent in July and August. It has a long duration and can take place for more than a week without interruption.

Figure 1: Map 9th of July 1999

Superficial thermical depression associated with a slight watercourse inside the high subtropical of the high layers of the atmosphere.

In the map corresponding to 18th of August of 1999, the jet stream continues travelling trough very high latitudes, but a small watercourse with its corresponding colder air irruption is moved up to latitudes near the 30°N parallel. In the ground, a thermical depression that extends the the Sahara depression, is installed over the South part of the peninsula introducing in Andalusia the continental tropical air mass with clear East wind flow. The heat is also intense in the region with these situations, although now the vertical air interchange is stronger due to the superficial depression and the less stability in altitude, what contributes to soften the thermical rigour. That donít stop the visibility reduction due to haze and the invasion of saharian dust. When the altitude watercourse is conveniently installed over the region favouring the superposition of cold air over superficial warm air, can originate convective outbreaks and storms, originating temperaure descendants and providing the few days with rainfall that can take place in our region during summer.

The establishment of the superficial thermical depression over Andalusia, as an extension of the Sahara one, is the most frequent situation in summer; in the opposite, due to our Southern position, the cold air packagement in altitude take place in very few occasions, specially in summer, what explains the prolongued and continue character of the summer drought, much important than in the other Spanish regions.

Figure 2: Map 18th of August 1999

Weather types dominant in winter.

During winter - the period between October and June - the synoptic situations are more varied, what explains the higher variability of the weather in this season. These variations are associated essentially to the behaviour of the West circumpolar flow, that can take three different shapes: zonal circulation, southern and cellular.

Weather types associated with the zonal circulation of the jet stream.

The most common fact is that the circulation get established in the North of the peninsula, travelling through its most southern part the 40-45° parallels (see map of the 8th of February of 2000). That determines that an important part of Spain (except made of the North face) and, of course, the Andalusian region, are under the influence of high pressures in altitude accompanied also in surface by an anticyclone extended in the sense of the parallels. The tropical marine or polar marine air, quite softenned, reaches our region favouring a sunny and stable weather, with the abscence of rainfalls and scarce or null cloudiness, except for the associated to the morning fog that favours the stability.

Figure 3: Map of the 8th of February of 2000

It is a persistent type of weather (it usually lasts more than five days) and, although it can take place in any month of the year, it has its higher frequency between December and March.

With much lower frequency, the West circumpolar flow is centered in the 35-40° parallels, travelling then the perturbations of the polar front all over the peninsula from West to East (map of the 25th of December 2000). In its southern face affects Andalusia and can produce rainfalls there, accompanied by soft temperatures deriving from the intervention over the region, also in this case, of marine tropical air masses quite softened due to its long oceanic journey. The frequency of this type of weather isn't high, but it can appear between December and February, favouring then the appearing of succesive rainy days with soft temperatures.

In some occasions the West circumpolar flow slightly waves and crosses the peninsula together with the perturbations of the polar front, in the NW-SE direction, staying the high pressures in a more occidental position. In these situations, the perturbations also sweep the region, even the South-East, although now the temperatures are lower than in the precedent weather type as a consequence of the more Northern trajectory of the marine polar air, the only one that now visit us.

Figure 4: Map of the 25th of December 2000

Weather types associated with the southern circulation of the jet stream.

The zonal circulation regimes of the jet stream, that corespond to high circulation levels, alternate with others in which the stream presents low circulation levels and adopts a southern position, drawing crests or watercourses more or less pronounced. The position of these crests and watercourses is determinant for the weather registered on it; the watercourses imply cold air advections and instability, which is specially pronounced in the West part; the anticyclonic crests transport warm air to high latitudes bringing an atmospheric stability regime, also specially pronounced in the West part. As a consequence of this asymmetry, distinction situations between West-East or oriental-occidental Andalusia are frequent, due to these situations.

In the map of the 2nd of April of 2000 the situation draws a watercourse over the peninsula, whith its central axis around the Cadiz Gulf. All Spain, and particularly the South-West, is under a strong instability, which is traduced, in surface, in a deep squall with its centre on the 45° parallel. Two very active cold fronts accompany it, sweeping the peninsula from the South-West to the North-East. On its begining, this squall channels tropical marine air proceeding from the South-West of Andalusia and favours realtively soft temperatures for the season, accompanied by intense rainfalls. After the passing of the fronts is the polar marine air, with a Noth-South trajectory, who becomes dominant, determining an abrupt descending of the temperatures. All the region is under rainfalls, which can be quite intense in the Cadiz Gulf, specially in the occidental mountainous places, where the shot effect due to the relief joins the thermodynamic effect.

Normally it isn't a persistent type of weather (3-4 days) neither frequent, taking place over all in Winter and the begining of Spring.

Figure 5: Map of the 2nd of April of 2000.

Another watercourse situation, but now located over the Mediterranean was registeredon the 8th of April of 1999. In this case, the maximum instability zone was in the oriental area of the peninsula, under the front face of the watercourse, what was reflected in the formation of a deep depression over the Genova Gulf. In the Atlantic, under the jet stream crest, a powerful blockade anticyclone (1032 hPa in its centre) was generated and between them a Noth and North-East flow was channeled transporting polar air to the peninsula, coming from the eurosiberian continent. The environment in the whole region was very cold and dry, the cloudiness was practically absent, except for the appearing of night irradiation fogs in the valleys, favoured by the atmospheric instability, and the minimum temperatures reached the lowest values of the region due to the pressence of the continental polar air mass and to the strong heat losses through irradiation, because there wasn't enough water vapour in the atmosphere to retain it.

It is a type of weather that usually last from three to five days and which frequency is important all around the year, except in summer.

Figure 6: Map 8th of April of 1999.

Weather types associated to the cellular circulation of the jet stream.

When the circulation index becomes quite low and the meanders described by the jet stream get very pronounced, cellular or closed circulations are formed, forming big warm anticyclones in altitude moved up to high latitudes and cold air depressions which locates in the lower latitudes. The stream has to leave this cold and warm air masses due to the pronounced meanders, getting reformed in northern latitudes. In these circumstances, Andalusia, because of its southern position, receives the influence of the coild air masses in altitude, gnerating a strong instability inmediately. In these conditions the so-called "mesoscale convective conjunctions", which are multicellular stormy developments with great extension (the radius is usually over 100 kms.), tend to form, normally with eccentricity on its radius and a duration much longer than the typical summer storms. These cloudiness formations, with a well organized structure, are generated from the coalescence of initial convective nucleus in an abundant water vapour in the atmosphere and strong instability context, features that characterize these altitude air masses that we were talking about.

Two are the preferent locations for the installation of these cold depressions: the Cadiz Gulf and the North of the Canary Islandas and the occidental Mediterranean. We have an example of the first case in the map of the 16th of January of 2000. On it, a pronounced wave in the jet stream leaves a blockage anticyclone in the North Atlantic and an important cold air mass between the Canary islands and the Cadiz Gulf. The closed in circles isohips around the depression and the very low temperature of the air on it configure this leave like a cut-off low, diagnosis confirmed by the scarce reflection of this leave on surface. In fact, in the surface map, a relative low pressure of 1012 hPa is located under the cut-off low. The pressure is like a normal pressure, but a well pronounced cyclonic curvature in the southern area of the peninsula has been generated, which, associated with the low altitude, will unleash an important instability, with the appearing of generalized rainfalls in Andalusia and specially around the Strait of Gibraltar.

Figura 7: Map 16th of January of 2000.

On the 12th of January of 2001, it is a separation of the jet stream what motivates the detachment of a cold depression to the South of the Iberian peninsula, centering this time over the Mediterranean. Its reflection on surface is now more pronounced than in the previous case, locating now a depression over the mediterranean peninsular coast. The forming of cold air masses in altitude, over the Mediterranean waters, relatively warm, generates a very instable vertical thermical gradient which, associated to the strong content of water vapour of the atmosphere, unleash intense rainfalls in all the peninsular East part, specially in the slopes situated at barlovent. The mediterranean Andalusia is now the most affected by the rainfalls, being the East part now under the protection of the Atlantic anticyclonic coast.

All these types that we've generically attributed to the winter season can take place in any of the months between October and June. We have to emphasize, however, that the southern and cellular circulations take special importance in the interseasons, when the readjustment between the summer and winter circulations of the jet stream and of all the action centres that accompany it takes place. These readjustments imply the formation of meanders in the west circumpolar flow, with crests and watercourses succeeding each other over the Andalusian territory. As a consequence the weather is usually more variable than in winter or summer, and the types of weather are also less persistent. In another side, it's frequent the alternation between springs and autumns that extend the previous season (dry autumns which extend summer typical situations aren't strange for the region, for example) with others that bring forward the season that goes after it (that would be the case of those autumns in which the rainfalls begin in September).

In a synthesis attempt of the situations that characterize each year's seasons, we can describe summer as the season under the predominance of anticyclonic situations, only with small and weak thermical depressions nearly without reflection on the weather, and as the season with the longer duration of the types of weather, which can last for two or three weeks continuously. In winter, the cyclonic and anticyclonic types have similar frequencies, around 50% each, and both acquire a strong intensity and a long duration. Spring registers the predominance of cyclonic situations, which are quite durable if we compaere them with the anticyclonic situations. The weather presents also a maximum variability, with less intense cyclonic types alternating with others more intense and with anticyclonic types. Finally, autumns is a transition season to winter and in that sense, it can be divided in two well differentiated parts: September and the begining of October, which tends to extend summer characteristics, and the second part of October and November, which have a behaviour similar to winter. In this season we have to emphasize the frequent appearing of pluviometric paroxisms associated to the pressence of cut-off low, veruy active at this time of the year as a consequence of the high temperatures reached in the Mediterranean. These high temperatures favour very instable vertical thermical gradients and an important water vapour and latent heat transfer to the atmosphere, all favouring the development of intense rainfalls.